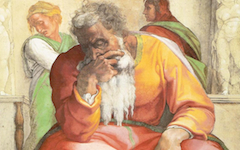

Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina (1504)

In the early years of the sixteenth century Michelangelo and Leonardo were each commissioned to paint a larger-than-life battle scene on the walls of the new Great Council Hall in Florence. The eminent Leonardo was 52, the young pretender Michelangelo 29. With the murals side-by-side they would have had to paint next to each other for several months though neither was completed, both artists called away to work on other projects. The cartoons [original full-scale studies] for both have been lost although a copy of what each would have looked like has survived. Leonardo’s study for the Battle of Anghiari appears to depict a fantastic, imaginary battle at close quarters. Michelangelo, to the subsequent consternation of art scholars, chose a stranger moment before the battle began when the soldiers were surprised by an attack while bathing in a river. What does it mean?

Antonio da Sangallo (attrib.), Copy after cartoon for Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina (1542)

Click image to enlarge.

Art historians have long thought that Michelangelo chose this moment before the battle when the soldiers were struggling to put on their clothes in order to display his skill at depicting the male nude. Kenneth Clark claimed that the scene had no meaning at all: "it was simply art for art's sake."1 James Hall, on the other hand, has insightfully observed that it "closely resembles a scene of the resurrection of the dead, when skeletons and bodies emerge from fissures in the ground."

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Michelangelo, The Punishment of Tityus (1532), detail

Bottom: Michelangelo, Bacchus (1496-8), detail

Click image to enlarge.

He's on the right track but the resurrection of the dead is used as a metaphor and not as the biblical event.

The fissures and faceted rock in The Battle of Cascina are not even unique to this piece but appear all over Michelangelo's work, from one of his earliest sculptures, Bacchus (bottom) to the late drawing of The Punishment of Tityus (top).

Click next thumbnail to continue

The figures in his two best-known masterpieces, the Virgin in the Pieta and David, also rest on faceted rock. And even in the Last Judgment, painted between 1536 and 1541, "the river Styx" at the bottom of the mural runs between two shores like a fissure in rock. Why?

Click next thumbnail to continue

Michelangelo's faceted rock is always, in my view, a visual metaphor for brain matter. As an expert anatomist he knew exactly what it looked like including the fissure between the two hemispheres. It was through that crack in the skull, known as the fontanelle, that the soul was thought to enter at birth. James Hall has separately noted how Michelangelo made a visual link between heads and rock in his very first sculpture.2

This raises another important issue. I do not believe Renaissance artists dissected corpses to draw more accurately. They looked inside because the body, made in the image of God, contained insights into the Divine and, as a literary critic has explained, was considered "a Second Scripture."3

See conclusion below

The Resurrection was a theme that obsessed Michelangelo throughout his career but, as a follower of the Inner Tradition, he thought of biblical events as internal allegories not external facts. The contract for The Last Judgment also stipulated that he should paint a Resurrection and I have shown elsewhere that he did indeed do so. He depicted that moment of spiritual perfection in the poet's mind when he becomes at one with God. In the Battle of Cascina, on the other hand, the figures put on clothes that resemble flesh5 because they are ideas in Michelangelo's mind coming to life, a metaphor for the creation of art. They emerge from the fontanelle in his brain or mind at a moment of spiritual perfection when the artist himself is, metaphorically at least, reborn as Christ.

Michelangelo would not have known the Gnostic Gospel of Philip which was rediscovered in the twentieth century but he would have appreciated its meaning from his close reading of Dante and the Bible. Saying 21 goes: "If men do not first experience the resurrection while they are alive, they will not receive anything when they die."6 It is resurrection in this life that is important, not the next. Besides, Christ's resurrection was always meant as a guide and a goal for living people, a message that the Establishment Church twisted into an article of faith around the 5th century. (See The Inner Tradition.)

For more on this interpretation see Mystery in Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina.

More Works by Michelangelo

Always look for what is odd. It's often there where you'll find a breakthrough in meaning

Michelangelo’s Christ in the Last Judgment (1534-41)

Notes:

1. Clark, The Nude (London: Harmondsworth) 1960, p.191

2. James Hall, Michelangelo and the Reinvention of the Human Body (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 2005, p.77

3. Eric F. Langley, “Anatomizing the early-modern eye: a literary case-study”, Renaissance Studies 20, June 2006, p. 347

4. Hall, p.87

5. Hall, p.87

6. Stephan A. Hoeller, . Gnosticism: New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing (Wheaton, IL: Quest Books) 2002, p.66

7. http://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/article/michelangelos_hands_in_battle_of_cascina_1504/

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 31 Jan 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.