Bellini’s Eyes (c.1450-1525)

This website, right or wrong about whether every painter paints himself, is still dedicated to pointing out the visual illusions in art which make it intriguing and interesting for the ordinary art lover. Who cannot marvel in the Sistine Chapel at the sight of Dante’s head fifteen feet tall over the high altar? Or Michelangelo's various anatomical organs on the ceiling? Portraits, once only of interest to the historically-minded, now grab the attention of everyone. What else do we not see besides the hundreds of other portraits with similar visual secrets known only to initiates, other artists? Most of the revelations here are undeniable whatever you make of their meaning. So, to keep this entry brief, we show a common feature of Giovanni Bellini’s art that no-one noted before.

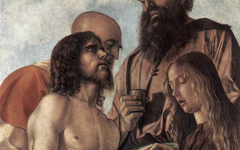

Any viewer sensitive to metamorphic form would recognize that a significant number of Giovanni Bellini’s paintings contain a giant “eye”, metaphorically expressed as a feature of the distant landscape, an opening in some ancient rockface, or as here at left the oculus above the Virgin’s head in the Frari Triptych. Oculus (Latin for eye) is even the architectural term for a dome like this. We have already shown in a separate entry how the viewer should read it as a giant "eye." Look carefully to see how the concave dome becomes a convex eye-ball pointing towards the heavens.

Twenty years earlier Bellini painted an Agony in the Garden in which features of the distant landscape suggest two giant “eyes”. At right concentric circles designate one of them while, at left, a hill reveals an open cliff-face somewhat like an eye face-on. Remember, two eyes in art are rarely the same – as Picasso once observed – because the right eye sees inwards while the left sees out. Here the "eyes" see two ways too, upwards and out at us with Jesus perhaps, disproportionately large, on the fragment of a nose.

Click next thumbnail to continue

L: Bellini, St Jerome Reading in the Countryside (1480-85) National Gallery, London

R: Bellini, St Jerome Reading (1480-90) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Click image to enlarge.

In a series of compositions of St. Jerome the saint sits next to a giant rock of a nose with the opening to the landscape as an eye. At far left the town wall suggests the edge of the pupil, the clouds an eyebrow.

In another version (1480-90), near left, the opening is even more like an eye with the dark green bush in the center as its dark but fertile pupil.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Bellini, St. Jerome in the Wilderness (c.1450) Barber Institute, Birmingham, UK

Click image to enlarge.

St Jerome is even the subject of Bellini’s earliest extant painting, said to have been created when he was just fifteen. Here the old man undeniably sits on the sculpted nostril of a giant nose in profile with no eyes visible. The lower half of this “face” is presumably underground. Opposite, though, a green and fertile hill suggests an eye looking out at us with the straight line of a wall through its pupil. This means that, as in The Agony in the Garden fifteen years later, "eyes" in the landscape face two ways even if those facing away from us in this painting are unseen.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Seventy-five years later Bellini painted one of his greatest masterpieces, St Francis in the Desert. Here I have long thought that the dark entrance to the cave on the far right represents an “eye” with some grapevines as its “eyebrow” above. A small gate guards it entrance where the saint normally studies. Now he has turned away from this "face" and towards God.

To repeat, interpretation is not my objective here. I merely want to point out what to artists is obvious: that many rocky backgrounds in Renaissance paintings are crumbling representations of giant "skulls" or "heads" within which the scene takes place. Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks, in both versions, is one such painting and we will present many more in the weeks to come.

More Works by Bellini

Notes:

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 11 Jul 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.