Quick Guide to the Sistine Chapel

One of the most exciting moments in the Sistine Chapel that anyone can experience is to see what art scholars never have: that dozens of figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment form the hidden profile of the painter’s poetic muse, Dante Alighieri, with his prominent nose and lantern jaw. Michelangelo knew Dante's Commedia by heart and even included Minos and Charon, fictional figures from the poem not in the Bible, at the bottom of the wall.1

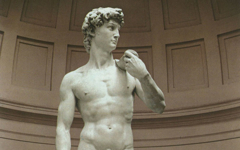

Top left: Michelangelo, Last Judgment

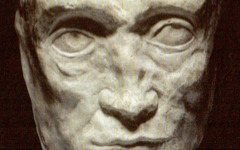

Top Right: Dante's Life-Mask

Bottom: Diagram of Dante's Profile in the Last Judgment

Click image to enlarge.

Compare the diagram (bottom) and Dante's life-mask (near left) with the Last Judgment (far left). If you cannot see Dante's profile even after you have enlarged the frame by clicking on it, click here instead and then return. Once it is recognized that the figure of a resurrected Christ is positioned in the center of a poet's brain, Michelangelo's meaning is clear: Dante as the artist's alter ego is undergoing a moment of creative inspiration, imagining, perhaps, the very image we are looking at.

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Michelangelo, Detail of The Creation of Adam

Bottom: Diagram of a cerebral hemisphere

Click image to enlarge.

On the ceiling God is in a human brain again because the cloak behind Him in the Creation of Adam is shaped like a cerebral hemisphere. That shape was recognized in 1990 by an American neurologist just as other doctors have recognized similar anatomical shapes elsewhere on the ceiling.2 By placing God inside the human mind, the artist rejects the Church's idea of an exterior God in favor of mystical Christianity's perennial knowledge that we ourselves become God. God is inside us.3

[It now seems quite possible that Michelangelo's conception of Adam's creation was inspired by Botticelli's masterpiece from 20 years earlier, The Birth of Venus (1484-6). See The Birth, Part Two.]

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Michelangelo, God Separating the Waters from the Firmament

Bottom: Diagram of a human kidney

Click image to enlarge.

All seven panels on the Creation are based on similar themes. A nephrologist recognized that the cloak behind God in an another panel was based on a kidney. Note how the pipes are reproduced in the rolls of God’s cloak. This cannot be coincidental because while kidneys were thought to separate matter from liquid in the Renaissance, the title of the panel is God Separating the Waters from the Firmament.4

Click next thumbnail to continue

Top: Michelangelo, Detail of Jonah panel

Bottom: Diagram of the human optical system

Click image to enlarge.

Jonah’s large figure sits above the Last Judgment and would have been the first form the Pope recognized on entering the Chapel. Today tourists enter from the other end. If the Pope understood art, he would have noticed that behind Jonah’s shoulder more pink cloth is shaped like an eye with a cornea in front and an optical nerve behind. The Cupid-like spiritello, is Michelangelo’s visualization of the nerves at work. It was thought that little spirits ran throughout our body telling the muscles what to do.5 Here he holds his opened palm in front of the “optical system” to signal that both craft (hand) and vision (eye) are needed to create art.

Click next thumbnail to continue

In another panel, God Creating the Plants (far left), the old man seems to float, his bottom exposed. Think, though, that you are on the floor looking up and you can imagine Michelangelo in the same position, sitting on a now-invisible stool or plank, painting the the ceiling. God is in the position Michelangelo once was, both in the act of creation. Jonah is similar (bottom). He, too, can be imagined in work clothes sitting on a plank, leaning back to get some paint. He is the artist, the most prominent figure in the whole room, painting the ceiling. Naturally, his attribute is the optical system combined with the spiritello's hand.

See conclusion below

In the longer version of this article and you will learn how Michelangelo turned the entire chapel into a representation of his own mind and body because, as Christian mystics have ever claimed and pagan ones before them, we are God.6 The human body is a microcosm of the macrocosm where everything in heaven can find its counterpart inside us. That’s why Michelangelo and Leonardo cut up cadavers. They were not trying to draw muscles more accurately – to do that, you need to look from the outside – but to search for the secrets of the cosmos. Besides, there is no choice between heaven and hell when we die, only inside us while we live. Man, as Adam, was made in the image of God and in leaving “the Garden of Eden” our eyes were closed to divine reality and consigned to a form of blindness that takes material reality for truth. Michelangelo repeats this process in the Chapel where the vast majority of viewers can only see the action he painted on the surface, failing to recognize the visual illusions where the truth of his message can be found.

More Works by Michelangelo

How we know that the young Picasso knew his destiny

Picasso’s Head of Picador with Broken Nose (1903)

Notes:

1. Dante's profile was first noted in a book published in 1954 by a Venezuelan diplomat, Joaquin Diaz Gonzalez. It has been mentioned only once by an art historian, in the footnotes to De Tolnay's multi-volume work on Michelangelo and he seemed unpersuaded. That was over half a century ago. In the late 1960's two literary critics both found the presence of Dante's profile "persuasive" though no art expert has either corroborated their view or even mentioned it except this writer. I have published the finding numerous times in The Art Newspaper and on the web but still no art historian can bring themselves to accept that academic art history, as currently practiced, is so profoundly mistaken. See Joaquin Diaz Gonzalez, Scoperta d’un grande segreto dell’art nel Giudizio Universale di Michelangelo, 2nd. ed. (Rome: Angelo Belardetti) 1954; Charles de Tolnay, Michelangelo: The Final Period (Princeton University Press) 1960; Gian Roberto Sarolli, “Michelangelo: The Poet of the Night”, Forum Italicum 1, Sept. 1967, pp. 153-4; Robert J. Clements, The Poetry of Michelangelo (New York: New York University Press) 1966, p. 317

2. Frank Lynn Meshberger, “An interpretation of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam Based on Neuroanatomy”, Journal of the American Medical Association 264, 1990, pp.1837-1841. His discovery has been widely published in the popular press but still no art historian has cited it.

3. Annie Besant, Esoteric Christianity, first publ. 1905, (Quest Books) 2006, pp. 17, 29, 32-33

4. Garabed Eknoyan,. “Michelangelo: Art, anatomy, and the kidney”, Kidney International 57, 2000, pp. 1190-1201

5. Charles Dempsey, Inventing the Renaissance Putto (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press) 2001, p.43

6. See Abrahams, "Michelangelo's Art Through Michelangelo's Eyes" at www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/essays

Original Publication Date on EPPH: 16 Feb 2011. | Updated: 0. © Simon Abrahams. Articles on this site are the copyright of Simon Abrahams. To use copyrighted material in print or other media for purposes beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Websites may link to this page without permission (please do) but may not reproduce the material on their own site without crediting Simon Abrahams and EPPH.